Hear What You See: The Introduction of Sound to Winnipeg’s Metropolitan Theatre

Note: I wrote this article as an undergrad in 2017 and have edited it for readability, though the citations remain unchanged and may be outdated.

While some aspects of Winnipeg’s movie theatre history have been extensively documented, little attention has been given to the very first introduction of sound cinema in a Winnipeg theatre. For a city often called a “cultural hub” of Canada, it is surprising that this event has gone undocumented and forgotten in the flow of time; this article attempts to correct that oversight and answer some of the most pressing questions surrounding the introduction of sound cinema to Winnipeg, exploring the conditions under which synchronised sound was adopted, what effect the Metropolitan Theatre’s 1928 conversion to sound actually had on Winnipeg’s cinema landscape at the time, and what happened in the years to come.

Winnipeg’s 2,000 seat Metropolitan Theatre was originally named the Allen Theatre, and was built in 1919 for Allen Theatre Enterprises—at that time, the most successful theatre chain in Canada—for $500,000 (about $7.7 million in 2023). The Allen Theatre opened on January 2, 1920 as a high-end, first-run cinema; like many cinemas of the time, the theatre housed an organ and an orchestra of twenty musicians, which provided live musical accompaniment for the silent films.¹ ² ³ There was often live entertainment between features as well, which included musical performances and English pantomimes.⁴ The Allen was the closest thing to a “movie palace” that Winnipeg had seen, with marble staircases, a fountain in the lobby, and a coloured-lighting system designed to reflect the mood of each scene that played on-screen.⁵ The projection equipment itself cost $15,000, and was located 102 feet from the “velvet gold fibre” screen to create a crisp 17-foot picture.⁶ Because of its fine amenities, the theatre was both a place for seeing motion pictures, and a place for socialising.

In 1919, Allen Theatre Enterprises cut their ties with Paramount Pictures and became freelance exhibitors. Rather than relying on the block-booking method which forced cinemas to show both the high- and low-quality films made by one production company, they could now play what they deemed to be the best films from all of the major production companies. At the height of their success, Allen Theatre Enterprises owned fifty-five theatres across the country, and it was because of their dominance in the Canadian industry that the chain was able to move away from block-booking. As an August, 1919 article in the Winnipeg Tribune stated, “For the first time in the annals of the motion picture industry of Canada, the exhibitor is independent of the producer.”⁷ This success did not last, however. In 1923, the company declared bankruptcy and was forced to sell its theatres to its main competitor, the Famous Players Canadian Corporation, which had become affiliated with Paramount after Allen discontinued their relationship with the production company in 1919.⁸ It was at this point that the Allen Theatre was renamed the Metropolitan Theatre and was briefly closed for slight aesthetic alterations.⁹ It now belonged to the same chain as its main competitor, the Capitol Theatre, which was built in 1921 and boasted similarly opulent internal features.¹⁰

Five years after its acquisition by Famous Players, the Metropolitan Theatre was positioned to become one of the first cinemas in the country to adopt synchronised sound. In 1928, Winnipeg was the fourth-largest city in the country, and Famous Players was spearheading the conversion to sound cinema.¹¹ The company owned the Palace Theatre in Montreal, the first cinema in Canada to introduce sound technology, as well as the three other theatres reported in September 1928 by the Exhibitors Herald to be doing the same.¹² A short article in the Winnipeg Evening Tribune in August of that year stated that the Metropolitan was to be the first in Western Canada to see the changes, though setbacks occurred.¹³ It was instead the fourth theatre, behind Vancouver and Toronto, to have Vitaphone and Fox Movietone installed by the Northern Electric Company. The Capitol was scheduled to undergo the same changes only months later.¹⁴ Thus, the Metropolitan was granted the privilege of introducing sound cinema to the citizens of Winnipeg for the very first time.

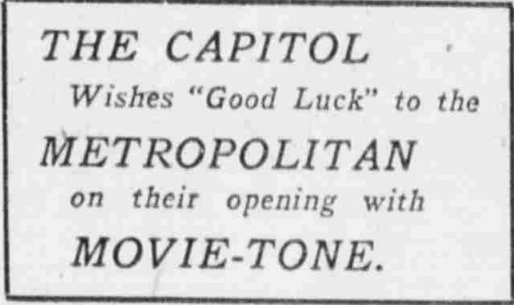

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 25, 1928. (University of Manitoba)

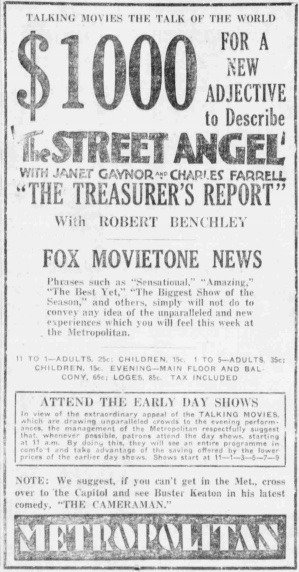

The event was heavily advertised in the local press in the weeks preceding the Metropolitan’s first sound-synchronised bill. The theatre was closed for a week during the installation of the technology—which cost $25,000—and it reopened on October 26, 1928, ready to present the new technological wonder to its prairie audience.¹⁵ Although it was equipped with both the Vitaphone and Fox Movietone systems, the first bill was made entirely for Movietone. It was the same as the bills presented at the three Famous Players theatres that installed sound technology prior to the Metropolitan, and the night began with the Frank Borzage-directed feature The Street Angel. This film did not contain any spoken words, but rather demonstrated the abilities of sound cinema through its sound effects and its score, which was recorded by the Roxy Orchestra in New York City. The short comedy that followed was an all-talking film called The Treasurer’s Report, and the night closed with the Fox Movietone News, which contained a selection of news items presented with sound.¹⁶ ¹⁷

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 27, 1928. (University of Manitoba)

Judging by newspaper reports from the following days, the program was very well-received. It appears that the “talkies” were indeed the talk of the town.¹⁸ While it could not definitively be proven three or four days after the initial showing, multiple articles asserted that the talking picture would soon become a fixture in all modern movie-houses. As one writer put it, the quality of the presentation was “too great and too universally appealing to prove anything but permanent.”¹⁹ Another reporter for the Winnipeg Evening Tribune remarked that the bill proved better upon each subsequent visit, while one columnist a week later stated that, “Talking movies, according to Winnipeg’s verdict in patronage this week, are here to stay.”²⁰ ²¹

There is evidence that moviegoers had some interest in how the sound systems actually worked, as a lengthy article on the topic ran the day after the inaugural screening, explaining the Movietone projection and amplification process in plain terms.²² While many, including those in charge of advertising for the Metropolitan, preferred to relate the technology to “Aladdin’s lamp” and “ancient magic”, this article suggested that the process was “more marvellous than the transmutation of metals, which the alchemists of old spent their lives to achieve.”²³ Ultimately, though, it seems that audiences were less interested in the science through which sound cinema was possible, and more interested in maintaining a romantic view of the cinematic experience. Like audiences of today, theatregoers were far more concerned with the “mood” and feeling that films evoked.²⁴ It is also interesting that although the Metropolitan was equipped with both Fox Movietone and Vitaphone, only the Movietone process was mentioned in the article, and only Fox features made for Movietone were presented in the first bill. This suggests that those in charge of programming for Famous Players sound bills at the time were already tending towards the sound-on-film method rather than sound discs; in fact, sound-on-film did eventually win the talkie battle, though the struggle continued for several years.

The rivalry between the Metropolitan and the Capitol—Winnipeg’s two “movie palaces”—was a friendly one, perhaps in part because both were owned by Famous Players. In an advertisement for the Capitol’s screening of Buster Keaton’s The Cameraman on October 27, 1928—the day after Winnipeg’s first sound show—the Capitol wished “good luck” to their competitor.²⁵ The kind sentiment was returned two days later by the Metropolitan, who ran an advertisement suggesting that audience members who could not gain admittance to the offerings at their establishment due to high attendance levels should instead see The Cameraman at the Capitol.²⁶ This suggestion was apparently so surprising that it was published in an American film exhibitors’ journal, and it not only illustrates the amicable relationship between the two cinemas, but also demonstrates the way the Metropolitan’s adoption of sound was able to benefit it competitors.²⁷

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 27, 1928. (University of Manitoba)

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 29, 1928. (University of Manitoba)

When the Capitol was finally ready to exhibit synchronised pictures in December of 1928, however, it had to distinguish itself from the present market to generate interest. As the Metropolitan was the only other theatre in the city that was wired for sound, it was important that the Capitol, a similarly upscale theatre, find a method of differentiation. The Metropolitan had not yet shown an all-talking feature film, and this became the main selling-point for the Capitol. As the second first-run cinema in Winnipeg to be equipped with Vitaphone and Movietone technology, the Capitol chose not to host a repeat of The Street Angel; instead, The Terror, a “100% all-talking feature” directed by Roy Del Ruth and produced by Warner Brothers, was screened on December 29, 1928, two months after the first sound film was shown to Winnipeg audiences.²⁸ At the time, the Metropolitan was playing Abie’s Irish Rose, a film directed by Victor Fleming that contained talking sequences and was based on a popular Broadway play, so perhaps the theatre’s administration did not see the Capitol’s bill as a significant threat.²⁹ The advertisements run by both theatres leading up to the event, however, possessed a hint of one-upmanship, with each cinema listing as many attractions as possible to draw audiences in. For the Metropolitan, it was a special midnight screening of their feature on New Year’s Eve, while the Capitol’s stage band, Earle Hill’s Capitolians, presented a stage-show called Hello 1929, with musical guests.³⁰ ³¹ It was indeed a significant date in Winnipeg’s cinema history as the first screening of an all-talking feature film, and the Capitol drew sufficient crowds to its premiere. However, the response was not quite as intense as the Metropolitan’s first screening, as the technology was already present in the city and had already been available to the public for two months.

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, December 27, 1928. (University of Manitoba)

While the introduction of sound to the Metropolitan Theatre was met with enthusiasm and excitement, the conversion process across the city was not as swift as one might assume. Theatre owners may have been sceptical of the technology at first, or hesitant to invest so much money in the process, though the Winnipeg Evening Tribune reported in early 1929 that the technology now cost only $3,500 to purchase and install.³² Regardless, three cinemas in the city had adopted sound by March of 1929, and silent cinemas still dominated the exhibition industry—Winnipeg and Ottawa were the only cities in the country to have three sound cinemas, and Canada as a whole had twenty cinemas equipped with the technology.³³ Sound cinema was predicted to make a permanent change to the film industry, and many were investing in it, yet five months after the Metropolitan’s inaugural screening, the technology was still somewhat uncommon in the Canadian theatre world.

Compared to the whole country, Winnipeg was indeed swift to adopt sound technology as a permanent fixture of its cinemas, especially at a time when information and physical objects took longer to transmit and transport across vast areas of land. However, from a broader perspective, and perhaps from one influenced by contemporary trends, sound cinema took much longer to catch on than many other historical innovations. It could not have been known just how much success synchronised sound would have in the film industry in coming years—some suggested that it would mainly be used to enhance non-talking films with sound effects and music—but Famous Players made what turned out to be a wise financial decision in initiating the conversion trend in Canada. As for the Metropolitan, its success with synchronised sound continued, and it apparently had so much faith in the technology that it discontinued its live orchestra in January of 1929.³⁴

The Metropolitan Theatre still exists in Winnipeg as a restaurant and an event space available for rentals. It closed as a movie theatre in 1987 due to competition from larger cinemas, and remained closed until November of 2012, when renovations were completed and it reopened. Much of the original architecture and decoration remains. The building is one of only a handful of Allen theatres that remain standing in the country, and it is the only former “movie palace” from the golden days of movie exhibition that still exists in Winnipeg.³⁵ The Capitol was renovated and converted to a double-theatre in 1979, and lost the impressive decoration and architecture that it once possessed. It was closed permanently in 1990, and the building was later torn down.³⁶

Winnipeg is now a city with a booming film industry and indispensable resources available for every level of filmmaker. The city’s cultural landscape has been shaped by its relationship with the international film industry at every step, and certainly, the introduction of sound cinema to the Metropolitan Theatre in 1928 is one of those steps that should not be ignored. Famous Players’ investment in sound technologies forever affected the way cinema is made and experienced, and Winnipeg’s citizens played a critical role in that investment, even if they did not recognize it at the time. It may be just a small element of Winnipeg’s historical relationship with film, but it clarifies everything else we already know about that relationship, and brings into perspective all we still have to learn.

Notes

"Interior of Allen Theatre is the Acme of Decorative Art; Has Every Modern Innovation." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, January 2, 1920. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1683877/datastream/PDF/view.

"Value of $500,000 from 1919 to 2023." DollarTimes. https://www.in2013dollars.com/canada/inflation/1919?amount=500000.

"Twenty-Piece Orchestra is Drawing Card." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, January 1, 1920. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1683879/datastream/PDF/view.

"English Pantomime, New Novelty at the Allen All Next Week." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, May 26, 1923. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1655601/datastream/PDF/view.

"Shades of Night--And Many Others." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, January 2, 1920. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1683877/datastream/PDF/view.

“Velvet Gold Fibre Screen." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, January 1, 1920. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1683879/datastream/PDF/view.

"Allens Adopt New Booking Policy," The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, August 30, 1919, http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1673464/datastream/PDF/view.

Moore, Paul. "Allen Theatres." Marquee 41, no. 3 (Fall 2009): 4-32. http://psmoore.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/3-2009-moore-dombowsky-marquee-allentheatres-part.pdf.

"Metropolitan, Formerly the Allen, Opens with Jackie Coogan as Star." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, July 21, 1923. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A2136704/datastream/PDF/view.

Irish, Chad and Andrew McCrea. "Capitol Theatre." Cinema Treasures. http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/2088.

Canada. Statistics Canada. Canada Year Book 1932. 103. https://www66.statcan.gc.ca/eng/acyb_c1932-eng.aspx?opt=/eng/1932/193201410103_p.%20103.pdf.

"Wire 4 Canadian Houses for Sound." Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World, September 29, 1928, 33. http://archive.org/stream/exhibitorsherald92unse#page/n1133/mode/2up.

""Talkies" Coming." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, August 25, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1745477/datastream/PDF/view.

"Toronto." Variety, August 1, 1928, 52. http://archive.org/stream/variety92-1928-08#page/n51/mode/2up.

"Talking Movies Open at Met. Next Saturday." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 20, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1746964/datastream/PDF/view.

Metropolitan Theatre. "To The Theatre-Going Public of Winnipeg." Advertisement. The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 26, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1747148/datastream/PDF/view.

"Huge Orchestra to Accompany Feature." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 25, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1747122/datastream/PDF/view.

N.B.Z. "Sound Pictures Have Premiere at Met. Friday." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 27, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1747195/datastream/PDF/view.

"Talking Movies Prove Instantaneous Hit." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 29, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1747244/datastream/PDF/view.

"Metropolitan." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 30, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1747280/datastream/PDF/view.

"Street Angel, Talking Films, Remain at Met." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, November 3, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1748145/datastream/PDF/view.

N.B.Z. "Screenings." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 27, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1747196/datastream/PDF/view.

Metropolitan Theatre. "Modern Miracles Beyond the Ken of Aladdin." Advertisement. The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 27, 1928.

"Street Angel, Talking Films, Remain at Met." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, November 3, 1928.

Capitol Entertainment. "The Cameraman." Advertisement. The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 27, 1928.

Metropolitan Theatre. "Talking Movies the Talk of the World." Advertisement. The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, October 29, 1928.

"Manager Advises Patrons to go to Competitor!" Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World, November 10, 1928, 39. http://archive.org/stream/exhibitorsherald93quig#page/n537/mode/2up.

Capitol Entertainment. "Talking Movies." Advertisement. The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, December 22, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1748745/datastream/PDF/view.

"Metropolitan." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, December 27, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1748877/datastream/PDF/view.

"Metropolitan." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, December 28, 1928. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1748911/datastream/PDF/view.

Capitol Entertainment. ""The Terror"." Advertisement. The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, December 28, 1928.

"Equipping a theatre for vitaphone..." The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, January 5, 1929. http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1749862/datastream/PDF/view.

"20 Theatres in Canada Showing Sound Films." Exhibitors Herald-World, March 23, 1929, 62. http://archive.org/stream/exhibitorsherald94quig#page/n1149/mode/2up.

"Six Film Houses Keep Musicians With Audiens." Exhibitors Herald-World, January 19, 1929, 43. http://archive.org/stream/exhibitorsherald94quig#page/n197/mode/2up.

"Winnipeg's Met Theatre set to reopen." CBCnews. November 30, 2012. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-s-met-theatre-set-to-reopen-1.1264346.

Irish, Chad and Andrew McCrea. "Capitol Theatre." Cinema Treasures.